Profile: Imo Nse Imeh. @Joey Kennedy

American Nigerian artist and scholar Dr. Imo Nse Imeh presents his current exhibition, The Sacred Story of Becoming, which opened at Ronewa Art Projects on December 18, 2025. His artistic practice explores themes of spirituality, cultural identity, memory, and the human figure through drawing, painting, and mixed media.

Roger Washington: You often position the human figure within environments shaped by ink, color, and layered marks. What guides the way you build these visual spaces, and how do they help you express the emotional or spiritual states you investigate?

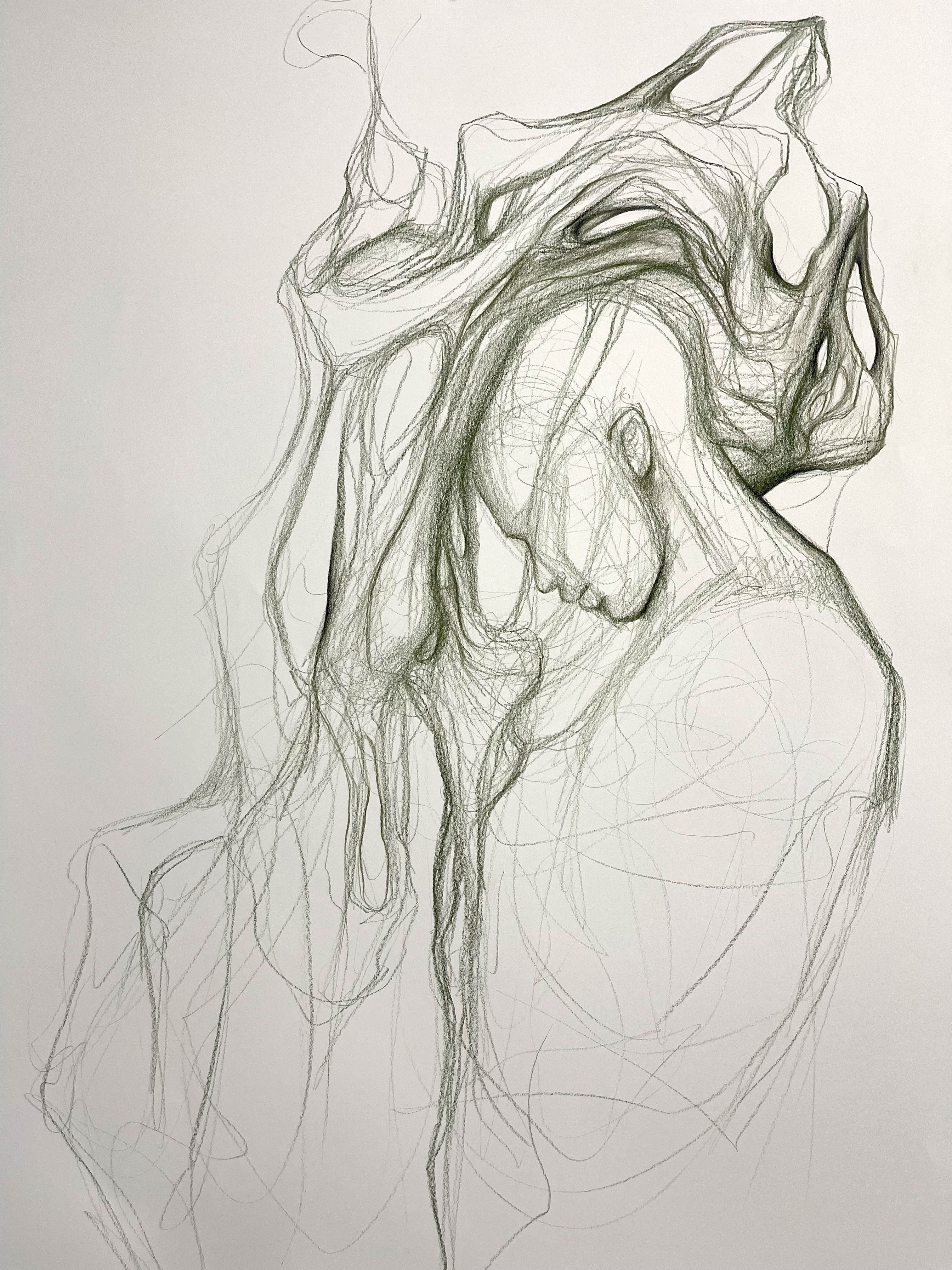

Imo Nse Imeh: Well, I think the best way to answer this question is to underscore the great significance that drawing, as a practice, has had on my approach to art making. Like many artists, I have enjoyed drawing since I was a child. But, as a professional artist, my process truly hinges on drawing as a primary foundation for my ideas-–that is to say, lines, linear forms, scribbles and markings, writing, and so forth, are key elements for me to build a dimensional narrative, creating depth in the work, and allowing the linear forms to remain as ghosts of the creation process. And so the visual spaces that I compose are largely orchestrated around my love for the types of stories that I can tell with lines.

The figure has been a central part of my artistic practice. I tell stories using the figure, and I tell stories about the figure in my work. So, the human form, like the practice of drawing, is also a very foundational component of my compositions; these two things together, linear forms and figural studies, are the building blocks for the worlds that I try to build and investigate, and the stories that I hope to communicate.

Over the years, India ink has become an aesthetic element in my work, the beautiful stains of which can be observed in many of my paintings. However, India ink has also served as a valuable artistic tool for me in helping to augment, partition, and reimagine spacesin my artwork. It has enabled me to partition the blank space of the canvas into enigmatic worlds in which I can situate figures and tell stories. My 2016 series Ten Little Nigger Girls was the first collection of works in which I employed India ink as a foundational material. This project is a retelling of a racist children’s book from 1907 in which ten Black girls are maimed or killed in the style of a nursery rhyme. In my retelling of this story, I discuss the real dangers of contemporary Black girls around the world. I limited myself to India ink and charcoal as foundational bases for this series. The India ink helped me to divide the space of the canvas into sections where I could begin to imagine the world in which these girls lived, and then create additional layers of information and story with charcoal and graphite. In this way, the amorphous nature of the ink and the shifty quality of the charcoal forced me to embrace the elements of the art process over which I lacked full control, but that were no less beautiful and impactful.

RW: You hold a Ph.D. in Art History and serve as a Professor of Art and Art History at Westfield State University. How does your academic research in African and African Diaspora art influence the ideas and decisions that shape your studio practice?

Imo Nse Imeh, Hightide, 2024, Oil paint, charcoal, oil pastel, India ink, acrylic ink, paper, mylar, unstretched canvas on gesso board, 76.2 x 76.2 cm (30 x 30 in), 82.5 cm x 82.5 cm, (32 1/2 in x 32 1/2 in) Framed

INI: As someone who loves the process of art making, and all of its surrounding atmosphere, but who has equally fallen in love with understanding the history of art and contextualizing my own work within the historical scope of cultural aesthetics and visual language, I have reconciled these two components of my identity as symbiotic—equal parts important to my development as a creative and scholar. However, I have confused art professionals, artists, and scholars alike over the years with my inherent duality. Many people question whether a great artist can also be an impactful art historian, and often, people within art and academic spaces have attempted to place me in a box of their own making. I am eternally grateful to the few who are my closest mentors and friends, who have encouraged me to lean into my braided identity of artist and scholar, because practicing both of these disciplines has made perfect sense to me, and has been a source of genuine joy as an adult creative.

I came to art history as a visual artist, and that will always be my story. I’ve remained planted in the world of art making because I can’t deny that part of myself. However, between my academic experiences as an undergraduate student at Columbia University, and as a graduate student at Yale University, some who oversaw my studies tried in earnest to convince me that I had to choose one over the other: art or art history. Personally, I have come to believe that many within academic spaces are unable to fathom the idea of a Black man behaving as both creator and interpreter of visual art forms. I happen to be both, and I’m really good at these two disciplines. I believe that my consistency as a practitioner of multiple disciplines in art and research scholarship has confounded a number of people who are unable to recognize their own prejudice in seeing the fullness of Black capacities in both artistic and scholastic achievement, and the numerous spaces of creativity and intellectualism that we as Black people are daring enough to occupy, and yes all at the same time.

RW: Your work reflects a sustained engagement with faith, ritual, and personal reflection. How does your spiritual life influence the themes you explore, and how do you translate these experiences into the visual structures of your paintings and drawings?

Imo Nse Imeh, Voyager (Poseidon's Maelstrom), 2024, Charcoal, India ink, acrylic ink, colored pencil, mylar, on gesso board, 76.2 x 101.6 cm, (30 x 40 in)

INI: One of the things that I’ve always hoped to achieve as an artist is to make the most ethereal and perhaps distant things tangible, physical. I believe in Almighty God, I believe in a spiritual realm that we don’t necessarily understand, but that exists and persists around us, and that informs many of our actions. So, as an artist, I feel like what I do is a translation of the spiritual space into something that I can touch, mold, and better comprehend. I see myself, in a way, as an intermediary between the world in which I occupy with everyone else, and the spiritual world. My desire as an artist has been to use my practice to deliver messages of hope and encouragement that come from realms that we may not be able to fully comprehend, but that are no less resonant and persistent in their capacity to change how we think, feel, and comport ourselves.

Even as a very young artist, I desired to transcribe, translate, or transmute prayers into art. Furthermore, I have always considered artistic creations as windows into other worlds, even those that we don’t necessarily understand. The concept has fascinated me as a student of art since childhood, and it is one of the ideas that eventually drew me into the study of art history, where I discovered that many visual artists think about art-making from this perspective. Of course, this idea of windows and portals existing through the works that we create is not novel. But I feel special being a part of a creative community of true believers in this idea that extends beyond cultural boundaries, and has proven to be timeless.

Moreover, I have also found intriguing the notion that the things I decide to create may have their own wills to exist and their own determination of their final appearances. The idea that as I am scribbling, sketching, or even writing, there may be forces bigger and greater than myself informing my hand movements, my thinking, my creativity is humbling. In this way, the materials that I frequently use in my practice are quite important. Charcoal cannot truly be fixed into place permanently. Even with spray varnishes, charcoal particles will eventually shift, disintegrate, and return to the earth. Oil Paint, regardless of how dry it might appear, is never truly dry–like charcoal, it is organic and in constant movement. These are things that cannot be controlled by the artist. In a similar vein, India ink that has been diluted with water cannot really be controlled by the artist. The ink and the water together move in the directions they decide, and dry in the patterns of their desire. As an artist, I can attempt to control these mediums with great frustration, or I can resolve to assist the creation in forming itself. In this way, I am in a constant state of becoming even as the artwork takes its completed form.

For me, abandoning myself to this reality means existing in the creative liminal space, a beautiful location between myself, a physical creator, and my persona as a cosmic dreamer.

RW: The exhibition is titled The Sacred Study of Becoming. How does your American Nigerian background shape the way you think about “becoming,” and how does this perspective inform your treatment of the human figure and the emotional tension present in these works?

Imo Nse Imeh, Yesterday/Tomorrow, 2024, Oil paint, India ink, acrylic ink, and charcoal on canvas, 121.9 x 121.9 cm, (48 x 48 in)

INI: One of the concepts that I explore in my recent work is this idea of “Home,” especially regarding “Home” as a physical location, or as a person, or as a community. Wrapped up in this thread of thought are ideas around citizenship, nationhood, and belonging. As an American-born man who is the son of Nigerian immigrants, these are questions that I have pondered for most of my life. Where, precisely, do I belong? Where am I fixed? Which culture should I lean into? Does it matter which language I am speaking or comprehending? As they routinely consume thinking, these questions and their accompanying ideas have become intertwined in my art.

The figures that I create are unfixed and itinerant. They move and shift from one location to the next, or between one figural representation to another. These figures are often in various states of transformation or becoming; in turn, they occupy liminal spaces in my work that are also transitional and in states of flux. In a number of works, the figures I create wind up defining the space in which they are situated. So, while a 'ground' might not be immediately evident in a work, the body of a seated figure, or one in repose, communicates to us that a ground exists.

I find these things interesting: the notion of space and its dedication around a figure, and the ways spaces can shift in design and composition, and the ways in which figures can morph or transcend into entirely new entities. I believe my implicit fascination with these concepts is very connected to the duality that I have in my own identity as an American-born Nigerian man. My culture is a significant part of who I am, even though I was born and raised in America. So, culturally, I sit in two spaces. In this way, there is sometimes a feeling of displacement in either culture because of a host of reasons that shift and change with time and my maturity. I have also witnessed this with my parents, who, in their old age, now long to return back 'Home' (to Nigeria). This longing is true and deep, even though all of their belongings and properties are here in the United States, and have been for many years. So, where is 'Home,' then? Is it where your belongings are housed, or is it where your fondest memories reside? These are lived experiences that are greatly influencing my current studio projects.

RW: The works in this exhibition span several years of your practice. What consistent concerns or evolving questions connect these ten pieces, and how do you see them speaking to each other across time?

Imo Nse Imeh, Sacrament, 2024, Charcoal, India ink, acrylic ink, colored pencil, paper, mylar, on gesso board, 76.2 x 76.2 cm (30 x 30 in). 82.5 cm x 82.5 cm. (32 1/2 in x 32 1/2 in) Framed

INI: These ten works are all connected by my desire to show in one part the vulnerabilities of Black men, and in another, the possibilities of Black men to exist in divine spaces and to house elements of divinity. All of these works see the Black male figure as beings who embody divinity and who exist in ethereal spaces. I feel the need to express that I am still seeking the language around the story of these beings, and I’m still developing the aesthetic vocabulary around the formal aspects of the figures that I am creating.

RW: You use canvas, paper, charcoal, ink, and layered paint throughout this body of work. What motivates your material choices, and how do these surfaces and mediums support the subjects and experiences you want to explore?

Imo Nse Imeh, Prayer Study, 2023, Crayon and colored pencil on paper, 111.8 x 83.8 cm, (44 x 33 in)

INI: I love to draw, and I love to work large, so canvas really lends itself to my practice. It has the capacity and durability to contain the layers of materials that I use to tell these stories. I also enjoy working with paper, though for my larger creations, working with unstretched canvas is more logistically sound. As I have previously mentioned, I thoroughly enjoy working with Indian ink and charcoal. In recent years, I’ve started layering oil paint over my charcoal forms, only to then add additional layers of charcoal over the oil paint. I have enjoyed how these two materials come together in my work. The interplay of the mediums has become emblematic of the ideas that I grapple with as an artist and hope to convey in my work.

The tension between these materials in my work—refined portraits and forms in oil, countered by dynamic and expressive linear forms—reflect the tensions that exist within Black identity. There are elements of Black identity that are strongly connected to the notion of becoming, or arrival, or transformation. And then there is this question of Black Diaspora identity, especially the questions: Where is home? Where are you located? Where do your feet land? Where have you been planted? Where do you grow? And I think the intertwining of these figural forms as charcoal renderings and oil paintings, while situating them in beautifully washed realms of ink, allows us to feel and experience the tensions of Blackness, and of really humanness as a whole. These are stories of the human experience. It is a magnificent thing that with tools of such simplicity, we are able to share our stories and live in each other’s wildly imaginative and spectacular spaces.

Access the the entire list of works by Imo Nse Imeh in our online viewing room and on Artsy.

• Artsy

Imo Nse Imeh

The Sacred Body of Becoming

December 18, 2025 - February 6, 2026

Ronewa Art Projects (Berlin)

Add a comment